Articles liés à Never Goin' Back: Winning the Weight-Loss Battle...

L'édition de cet ISBN n'est malheureusement plus disponible.

Afficher les exemplaires de cette édition ISBNBook by Roker Al Morton Laura

Les informations fournies dans la section « Synopsis » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

Extrait :

July 2001

My father had been at Memorial Sloan-Kettering hospital in New York City for about a

week, battling his final stages of lung cancer. Although he had been a smoker early in his

life, he had given up cigarettes cold turkey some thirty-five years prior to his cancer

diagnosis. So when he was told that he had stage four lung cancer, I wasn’t emotionally

prepared. Our entire family was shaken up and took his diagnosis very hard.

Al Roker Sr. was the rock of our family. Even though he was a talented artist, in the

mid-1950s, it was difficult for a young African-American male to get a job in the

commercial art industry. After a short stint at a low-paying apprentice job with no chance

for advancement, with a young wife and a new baby to feed, Dad got a job driving a New

York city bus.

He would do that for almost twenty years, always looking for the next step up.

Eventually he made dispatcher, then chief dispatcher, and then he was promoted up and into

management with the Metropolitan Transit Authority, reaching the rank of Inspector.

We were all so proud of him. His drive and determination rubbed off on his children. We

would strive to make him and our mother as proud of us as we were of them.

When he retired, he was excited and determined to enjoy life. My dad found pleasure in

being with his wife and his grandchildren, and in his lifelong hobby of deep-sea fishing.

He cultivated a newfound love of jazz, started a mentoring program for middle schoolers at

a local public school and walked with a group of fellow retirees at the local mall.

But all of that was now behind him. His entire future had now collapsed into being

measured by weeks, if not days.

Every day I made it a point to stop in, first thing in the morning, before heading to

the studio to do the Today show. We’d visit, and then about six twenty a.m., I’d

head on to Studio 1-A in Rockefeller Plaza, where the show goes live at seven a.m. On my

way home in the afternoon, I’d head straight back to the hospital to spend more time with

him—time, something I had all but taken for granted until my father got sick.

Time.

Why hadn’t I gone fishing with him more than a handful of times, and why didn’t I come

by the house more often? I always thought I would have plenty of time.

My father was always healthy as a horse. Mom was the one who had beaten lung cancer and

breast cancer and survived two heart valve replacements! Dad almost never got sick. Now he

was dying and I had just about run out of time with the man I cherished most in life.

There was nowhere near enough time.

“Son,” my dad said one day, “I’d do anything for more time. I wanted to make fifty

years of marriage with your mom so, yeah, I’m pissed about that.”

It was kind of funny, actually. My father always liked things well-ordered and tidy. He

was sixty-nine years old and had been married forty-nine years. To him, seventy and fifty

felt neater—more complete.

I knew my dad was going to die. There was no hope that he could possibly recover. I did

my best to hold myself together until one morning I simply couldn’t hide my grief about

losing him. I started crying, and being the incredible father he was, he comforted me.

He said he was proud of the life he had lived—that he’d had a good run. He told me he

was proud of his children and he loved his grandchildren more than life itself. Hearing my

father speak that way was simply more than I could bear; it was all so final. My tears

kept coming. I could tell that my father had something important he wanted to say.

“Look, we both know that I’m not going to be here to help you raise my grandkids, so

that means it is up to you to make sure you will be there for your kids.”

I could feel my heart begin beating faster with every word he uttered because I knew

what he was driving at. My father and I had been around the horn too many times to count

on the subject of my weight and overall health. For whatever reason, no matter how many

times I said I’d lose the weight, I couldn’t—or wouldn’t, or did only to gain it back

again.

“Promise me that you are going to lose the weight.”

I tried to play it off like it was no big deal. “Who, me? I’m fine! Don’t worry about

me, Dad.”

I could tell he was really struggling to get the words out now. “No, not good enough. I

want you to swear to God that you’re going to lose the weight.”

I realized there was really only one respectable thing to do—promise him I would lose

the weight.

Ugh.

Now, I don’t know if you’ve ever had to make a deathbed promise to someone you love,

but if you have, you know the kind of guilt and massive responsibility I felt in that

moment. And if you haven’t, let me assure you, it was heavy—heavier than me, and I was

damn big. I couldn’t say a word. It wasn’t that I didn’t want to, because I did, but I was

hesitant. Nothing I could say would mean all that; I had said it all before, without ever

doing the work to permanently change my mind-set and lose the weight for good.

So, I promised him I would lose the weight. Still, that wasn’t good enough for him. He

wanted me to swear to God that I was going to lose the weight—and so I did.

“Dad, I swear to God I am going to lose this weight.”

“I am going to hold you to that son. You don’t want to make me angry.”

Trust me, I didn’t want to get him angry.

I remember when I was twelve years old and my folks had gotten me a brand-new Sting-Ray

bicycle for my birthday. It had a banana seat and a metallic blue paint job. I loved that

bike!

Well, one Saturday afternoon, some young thugs from outside our neighborhood came

cruising through. They surrounded me, punched me a few times, knocked me off the bike and

took it. My pride was hurt more than anything else, but when I got home and told my dad

what happened, I saw a look come over him that I had never seen. “Get in the car. Let’s go

look for your bike,” he said through clenched teeth. He got behind the wheel and I got in

on the passenger’s side and we went looking for these guys and my bike.

After around fifteen minutes of driving around, I noticed a dishtowel wrapped around

something sitting on the seat between the two of us. I unwrapped an edge of the towel and

saw a steak knife! Dad was going to find that bike and was prepared to fight anyone

who got in his way. That’s who my dad was. We never actually found the bike but I

discovered I loved my father that day even more than I knew because of his willingness to

protect who and what he loved.

He was also the same man who cried when he deposited his firstborn son at the dorm on

my first day of college. Everything he was made me who I am.

And now that was all about to go away.

So on the morning I made that promise to my dad, I left the hospital thinking about

what he had said—a lot. I don’t usually get distracted when I am on the air, but his words

echoed in my mind the entire show. I was so upset about my promise to lose weight, in

fact, that I had two grilled cheese and bacon sandwiches for lunch. My mantra at the time

was “When in doubt, eat.”

When I returned to the hospital that afternoon, Dad was out of his bed, sitting up in a

chair.

“Hey, old man, how you doing?” I said, but there was no response. He was just looking

off into space. One of the nurses came in and told me he’d suddenly stopped talking

earlier that day.

“Why?” I asked. The nurse said she would get one of his doctors to explain what was

going on. You know it’s always bad news when someone says they want to get someone else to

explain things to you. In other words: “Here comes bad news and they don’t pay me enough

to put up with the grief you will probably give me!”

When the doctor arrived, he said that my dad’s cancer had spread to his brain. It was

affecting his ability to speak and would likely impair his motor functions very soon.

As I helped the doctor and the nurse transfer my father back into bed, he lost control

of his bowels. He couldn’t say anything, but the look on his face was heartbreaking. My

father, the strongest man I knew, both physically and emotionally, was leaving. And there

was nothing I could do about it.

A couple of weeks earlier, planning for this moment, my family had made the decision to

move dad, when the time came, to Calvary Hospital in the Bronx. It is the world leader in

palliative care, run by the Archdiocese of New York.

Two days later we transferred him to Calvary, where angels do heaven’s work on earth

and where he would spend his final days. My brother and sisters all came to say good-bye

to their father. Our spouses sat by his bed. His grandchildren were there. And we all

hugged and held my mother as she watched her husband slip away.

That week was a blur, but I can tell you just about the entire menu at the Calvary

cafeteria. I was aware that I was using food to ease the pain, but I didn’t care. As we

all kept vigil by my dad’s side, I kept thinking about the promise I had made to him and

wondering, “How the hell am I going to do this?”

Chapter One

A Portly Kid from Queens

I was born in Queens, New York, in 1954. I am the oldest of six kids, three boys and

three girls. Three of us are the biological children of my parents and three were adopted

through foster care. I am one of the biological kids, along with a sister who’s six years

younger and a “baby” brother, who is seventeen years younger than me. Although I was a

premature baby, weighing in at four pounds, ten ounces, at a certain point very early in

my life, I just started eating and never stopped. I suppose my family heritage added to my

genetic lot in life. Both of my parents came from families who loved to eat. My mom,

Isabel, also known as “Izzy,” was Jamaican, and my dad was from the Bahamas. Dad looked

like a young Sidney Poitier, who happened to be from Exuma, the same island in the Bahamas

where my father’s family was from. When my dad was younger, people often did a double take

when they saw him driving his white Plymouth Valiant station wagon—the same car Sidney

Poitier drove in Lilies of the Field.

My parents met at John Adams High School in Queens. My mother was one of the first

African-American cheerleaders at the school—at the time, a very big deal. She must have

loved being a cheerleader because I grew up hearing a constant chant of “Rickity, rackity,

shanty town. Who can knock John Adams down? Nobody. Nobody. Absolutely nobody! Yeah,

team!” Honestly, I can’t believe I still remember her saying that, but I do!

My dad was an affable guy and a really sharp dresser. He was a very good storyteller

who enjoyed sharing tales from his younger days. Turns out, my dad was a stone-cold thug!

He had friends with names like Deadeye and Jelly Roll. He had a walking stick that had a

knife in it.

Yeah, growing up, he was a tough guy. But by the time his children came along, he was a

short, stocky teddy bear. (I like to say I come from stocky people, low to the ground,

with one leg shorter than the other, the better to lean into the wind and survive

hurricanes.) Of my parents, Dad was definitely the gentler one. If you fell and skinned a

knee, you went right to Dad. He’d comfort you and give you a big bear hug, whereas Mom was

more likely to tell us to stop crying. Her approach was the early version of “man up.”

You might say Izzy was the original Tiger Mom. She was tough as nails and,

unlike a lot of women of her generation, she enjoyed confrontation. To her, it was sport.

I knew I was loved by her, but she knew exactly how to needle me, and what drove me crazy.

Whenever she’d come to my house for dinner, just as I was serving the meal, she’d ask,

“Is this any good?”

“No, I just spent an hour making you something that tastes like crap!” I’d respond.

Mom loved to banter and was a real jokester. She was also honest to a fault and didn’t

believe in coddling. She taught my younger daughter, Leila, to play checkers as a kid.

Most grandparents let the kids win—but not my mom. No way. To her, losing is how you

learn. And now I call Leila “little Izzy” because she is so much like my mom. I once

overheard her playing Monopoly with some of her friends. She wiped the board. Then one of

her friends asked, “Where’d you learn how to play Monopoly?”

“My nana,” Leila said with great pride. I couldn’t help but smile.

I was what you might call a late bloomer. As hard as this might be to believe today, I

didn’t talk until I was three and a half years old. Of course, as a family friend pointed

out later, I could never get a word in edgewise anyway! My mom did all the talking for me.

She was like my PR agent.

Although I was born premature, I think my lack of development was a combination of

being extremely shy—something I never really outgrew and what today might be labeled as a

learning disorder. And I might have had one. The only thing I had no problems learning was

eating. Well, maybe I had one issue I didn’t learn, and that was when to stop.

Although my siblings and I have the same father, he was really two different guys over

the years. My dad drove a bus and was a blue-collar worker. He hustled every day to

provide for his family. When I was a young boy, he and a couple of buddies from NYC

Transit, as it was then known, opened up a luncheonette in the depot. They made and sold

sandwiches in addition to working their regular shifts. My dad was the kind of man who did

whatever it took to make sure his family had everything we needed. In a Caribbean family,

if you only had two jobs, you were obviously slacking off.

But the drivers all had their rackets going to supplement their incomes. For

example, there was always someone selling hot merchandise—you know, things they claimed

fell off the back of a truck somewhere. In fact, I bought my first movie camera, which

sparked my initial interest in animation and television, from one of the guys at the

depot.

Unlike a lot of men from that era, my father was very demonstrative; he was a big

hugger and kisser. When I saw my uncles and cousins, my impulse was to greet them with a

bear hug and a kiss, while they usually held out their hands waiting for a handshake.

There was a lot of PDA in my parents’ household. And I remember coming home from college

to find my mother in the kitchen doing dishes.

“How would you feel about another brother or sister?” she asked.

“Are you going to adopt again?”

“No.”

“Oh, then we’re taking in another foster kid?”

“No . . .” she replied, and then paused.

Not adopting. No foster kid. . . . Oh for the love of . . . I didn’t want to think

about that! They’re my parents, for Pete’s sake!

Mom always wanted a big family. She was the second youngest of nine kids, so a big

family is all she knew. After she had me and my sister, she had trouble getting pregnant,

so she and my dad decided to adopt and open their home to numerous foster children over

the years. While sometimes people refer to foster or adopted children as half brothers and

half sisters, to me they are my siblings. Needless to say, it came as something of a

surprise when she got pregnant seventeen years after having me.

By the time my baby brother was born, Dad had transitioned from blue-collar worker to

white-collar executive. He had been promoted and was working in management for the New

York Transit Authority. He had an of...

Présentation de l'éditeur :

My father had been at Memorial Sloan-Kettering hospital in New York City for about a

week, battling his final stages of lung cancer. Although he had been a smoker early in his

life, he had given up cigarettes cold turkey some thirty-five years prior to his cancer

diagnosis. So when he was told that he had stage four lung cancer, I wasn’t emotionally

prepared. Our entire family was shaken up and took his diagnosis very hard.

Al Roker Sr. was the rock of our family. Even though he was a talented artist, in the

mid-1950s, it was difficult for a young African-American male to get a job in the

commercial art industry. After a short stint at a low-paying apprentice job with no chance

for advancement, with a young wife and a new baby to feed, Dad got a job driving a New

York city bus.

He would do that for almost twenty years, always looking for the next step up.

Eventually he made dispatcher, then chief dispatcher, and then he was promoted up and into

management with the Metropolitan Transit Authority, reaching the rank of Inspector.

We were all so proud of him. His drive and determination rubbed off on his children. We

would strive to make him and our mother as proud of us as we were of them.

When he retired, he was excited and determined to enjoy life. My dad found pleasure in

being with his wife and his grandchildren, and in his lifelong hobby of deep-sea fishing.

He cultivated a newfound love of jazz, started a mentoring program for middle schoolers at

a local public school and walked with a group of fellow retirees at the local mall.

But all of that was now behind him. His entire future had now collapsed into being

measured by weeks, if not days.

Every day I made it a point to stop in, first thing in the morning, before heading to

the studio to do the Today show. We’d visit, and then about six twenty a.m., I’d

head on to Studio 1-A in Rockefeller Plaza, where the show goes live at seven a.m. On my

way home in the afternoon, I’d head straight back to the hospital to spend more time with

him—time, something I had all but taken for granted until my father got sick.

Time.

Why hadn’t I gone fishing with him more than a handful of times, and why didn’t I come

by the house more often? I always thought I would have plenty of time.

My father was always healthy as a horse. Mom was the one who had beaten lung cancer and

breast cancer and survived two heart valve replacements! Dad almost never got sick. Now he

was dying and I had just about run out of time with the man I cherished most in life.

There was nowhere near enough time.

“Son,” my dad said one day, “I’d do anything for more time. I wanted to make fifty

years of marriage with your mom so, yeah, I’m pissed about that.”

It was kind of funny, actually. My father always liked things well-ordered and tidy. He

was sixty-nine years old and had been married forty-nine years. To him, seventy and fifty

felt neater—more complete.

I knew my dad was going to die. There was no hope that he could possibly recover. I did

my best to hold myself together until one morning I simply couldn’t hide my grief about

losing him. I started crying, and being the incredible father he was, he comforted me.

He said he was proud of the life he had lived—that he’d had a good run. He told me he

was proud of his children and he loved his grandchildren more than life itself. Hearing my

father speak that way was simply more than I could bear; it was all so final. My tears

kept coming. I could tell that my father had something important he wanted to say.

“Look, we both know that I’m not going to be here to help you raise my grandkids, so

that means it is up to you to make sure you will be there for your kids.”

I could feel my heart begin beating faster with every word he uttered because I knew

what he was driving at. My father and I had been around the horn too many times to count

on the subject of my weight and overall health. For whatever reason, no matter how many

times I said I’d lose the weight, I couldn’t—or wouldn’t, or did only to gain it back

again.

“Promise me that you are going to lose the weight.”

I tried to play it off like it was no big deal. “Who, me? I’m fine! Don’t worry about

me, Dad.”

I could tell he was really struggling to get the words out now. “No, not good enough. I

want you to swear to God that you’re going to lose the weight.”

I realized there was really only one respectable thing to do—promise him I would lose

the weight.

Ugh.

Now, I don’t know if you’ve ever had to make a deathbed promise to someone you love,

but if you have, you know the kind of guilt and massive responsibility I felt in that

moment. And if you haven’t, let me assure you, it was heavy—heavier than me, and I was

damn big. I couldn’t say a word. It wasn’t that I didn’t want to, because I did, but I was

hesitant. Nothing I could say would mean all that; I had said it all before, without ever

doing the work to permanently change my mind-set and lose the weight for good.

So, I promised him I would lose the weight. Still, that wasn’t good enough for him. He

wanted me to swear to God that I was going to lose the weight—and so I did.

“Dad, I swear to God I am going to lose this weight.”

“I am going to hold you to that son. You don’t want to make me angry.”

Trust me, I didn’t want to get him angry.

I remember when I was twelve years old and my folks had gotten me a brand-new Sting-Ray

bicycle for my birthday. It had a banana seat and a metallic blue paint job. I loved that

bike!

Well, one Saturday afternoon, some young thugs from outside our neighborhood came

cruising through. They surrounded me, punched me a few times, knocked me off the bike and

took it. My pride was hurt more than anything else, but when I got home and told my dad

what happened, I saw a look come over him that I had never seen. “Get in the car. Let’s go

look for your bike,” he said through clenched teeth. He got behind the wheel and I got in

on the passenger’s side and we went looking for these guys and my bike.

After around fifteen minutes of driving around, I noticed a dishtowel wrapped around

something sitting on the seat between the two of us. I unwrapped an edge of the towel and

saw a steak knife! Dad was going to find that bike and was prepared to fight anyone

who got in his way. That’s who my dad was. We never actually found the bike but I

discovered I loved my father that day even more than I knew because of his willingness to

protect who and what he loved.

He was also the same man who cried when he deposited his firstborn son at the dorm on

my first day of college. Everything he was made me who I am.

And now that was all about to go away.

So on the morning I made that promise to my dad, I left the hospital thinking about

what he had said—a lot. I don’t usually get distracted when I am on the air, but his words

echoed in my mind the entire show. I was so upset about my promise to lose weight, in

fact, that I had two grilled cheese and bacon sandwiches for lunch. My mantra at the time

was “When in doubt, eat.”

When I returned to the hospital that afternoon, Dad was out of his bed, sitting up in a

chair.

“Hey, old man, how you doing?” I said, but there was no response. He was just looking

off into space. One of the nurses came in and told me he’d suddenly stopped talking

earlier that day.

“Why?” I asked. The nurse said she would get one of his doctors to explain what was

going on. You know it’s always bad news when someone says they want to get someone else to

explain things to you. In other words: “Here comes bad news and they don’t pay me enough

to put up with the grief you will probably give me!”

When the doctor arrived, he said that my dad’s cancer had spread to his brain. It was

affecting his ability to speak and would likely impair his motor functions very soon.

As I helped the doctor and the nurse transfer my father back into bed, he lost control

of his bowels. He couldn’t say anything, but the look on his face was heartbreaking. My

father, the strongest man I knew, both physically and emotionally, was leaving. And there

was nothing I could do about it.

A couple of weeks earlier, planning for this moment, my family had made the decision to

move dad, when the time came, to Calvary Hospital in the Bronx. It is the world leader in

palliative care, run by the Archdiocese of New York.

Two days later we transferred him to Calvary, where angels do heaven’s work on earth

and where he would spend his final days. My brother and sisters all came to say good-bye

to their father. Our spouses sat by his bed. His grandchildren were there. And we all

hugged and held my mother as she watched her husband slip away.

That week was a blur, but I can tell you just about the entire menu at the Calvary

cafeteria. I was aware that I was using food to ease the pain, but I didn’t care. As we

all kept vigil by my dad’s side, I kept thinking about the promise I had made to him and

wondering, “How the hell am I going to do this?”

Chapter One

A Portly Kid from Queens

I was born in Queens, New York, in 1954. I am the oldest of six kids, three boys and

three girls. Three of us are the biological children of my parents and three were adopted

through foster care. I am one of the biological kids, along with a sister who’s six years

younger and a “baby” brother, who is seventeen years younger than me. Although I was a

premature baby, weighing in at four pounds, ten ounces, at a certain point very early in

my life, I just started eating and never stopped. I suppose my family heritage added to my

genetic lot in life. Both of my parents came from families who loved to eat. My mom,

Isabel, also known as “Izzy,” was Jamaican, and my dad was from the Bahamas. Dad looked

like a young Sidney Poitier, who happened to be from Exuma, the same island in the Bahamas

where my father’s family was from. When my dad was younger, people often did a double take

when they saw him driving his white Plymouth Valiant station wagon—the same car Sidney

Poitier drove in Lilies of the Field.

My parents met at John Adams High School in Queens. My mother was one of the first

African-American cheerleaders at the school—at the time, a very big deal. She must have

loved being a cheerleader because I grew up hearing a constant chant of “Rickity, rackity,

shanty town. Who can knock John Adams down? Nobody. Nobody. Absolutely nobody! Yeah,

team!” Honestly, I can’t believe I still remember her saying that, but I do!

My dad was an affable guy and a really sharp dresser. He was a very good storyteller

who enjoyed sharing tales from his younger days. Turns out, my dad was a stone-cold thug!

He had friends with names like Deadeye and Jelly Roll. He had a walking stick that had a

knife in it.

Yeah, growing up, he was a tough guy. But by the time his children came along, he was a

short, stocky teddy bear. (I like to say I come from stocky people, low to the ground,

with one leg shorter than the other, the better to lean into the wind and survive

hurricanes.) Of my parents, Dad was definitely the gentler one. If you fell and skinned a

knee, you went right to Dad. He’d comfort you and give you a big bear hug, whereas Mom was

more likely to tell us to stop crying. Her approach was the early version of “man up.”

You might say Izzy was the original Tiger Mom. She was tough as nails and,

unlike a lot of women of her generation, she enjoyed confrontation. To her, it was sport.

I knew I was loved by her, but she knew exactly how to needle me, and what drove me crazy.

Whenever she’d come to my house for dinner, just as I was serving the meal, she’d ask,

“Is this any good?”

“No, I just spent an hour making you something that tastes like crap!” I’d respond.

Mom loved to banter and was a real jokester. She was also honest to a fault and didn’t

believe in coddling. She taught my younger daughter, Leila, to play checkers as a kid.

Most grandparents let the kids win—but not my mom. No way. To her, losing is how you

learn. And now I call Leila “little Izzy” because she is so much like my mom. I once

overheard her playing Monopoly with some of her friends. She wiped the board. Then one of

her friends asked, “Where’d you learn how to play Monopoly?”

“My nana,” Leila said with great pride. I couldn’t help but smile.

I was what you might call a late bloomer. As hard as this might be to believe today, I

didn’t talk until I was three and a half years old. Of course, as a family friend pointed

out later, I could never get a word in edgewise anyway! My mom did all the talking for me.

She was like my PR agent.

Although I was born premature, I think my lack of development was a combination of

being extremely shy—something I never really outgrew and what today might be labeled as a

learning disorder. And I might have had one. The only thing I had no problems learning was

eating. Well, maybe I had one issue I didn’t learn, and that was when to stop.

Although my siblings and I have the same father, he was really two different guys over

the years. My dad drove a bus and was a blue-collar worker. He hustled every day to

provide for his family. When I was a young boy, he and a couple of buddies from NYC

Transit, as it was then known, opened up a luncheonette in the depot. They made and sold

sandwiches in addition to working their regular shifts. My dad was the kind of man who did

whatever it took to make sure his family had everything we needed. In a Caribbean family,

if you only had two jobs, you were obviously slacking off.

But the drivers all had their rackets going to supplement their incomes. For

example, there was always someone selling hot merchandise—you know, things they claimed

fell off the back of a truck somewhere. In fact, I bought my first movie camera, which

sparked my initial interest in animation and television, from one of the guys at the

depot.

Unlike a lot of men from that era, my father was very demonstrative; he was a big

hugger and kisser. When I saw my uncles and cousins, my impulse was to greet them with a

bear hug and a kiss, while they usually held out their hands waiting for a handshake.

There was a lot of PDA in my parents’ household. And I remember coming home from college

to find my mother in the kitchen doing dishes.

“How would you feel about another brother or sister?” she asked.

“Are you going to adopt again?”

“No.”

“Oh, then we’re taking in another foster kid?”

“No . . .” she replied, and then paused.

Not adopting. No foster kid. . . . Oh for the love of . . . I didn’t want to think

about that! They’re my parents, for Pete’s sake!

Mom always wanted a big family. She was the second youngest of nine kids, so a big

family is all she knew. After she had me and my sister, she had trouble getting pregnant,

so she and my dad decided to adopt and open their home to numerous foster children over

the years. While sometimes people refer to foster or adopted children as half brothers and

half sisters, to me they are my siblings. Needless to say, it came as something of a

surprise when she got pregnant seventeen years after having me.

By the time my baby brother was born, Dad had transitioned from blue-collar worker to

white-collar executive. He had been promoted and was working in management for the New

York Transit Authority. He had an of...

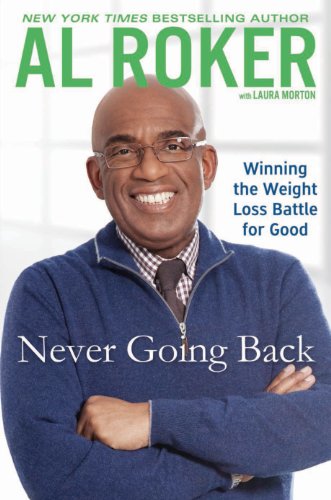

Al Roker’s aha! moment came a decade ago. He was closing in on 350 pounds when he promised his dying father that he wasn’t going to keep living as he was. That led to his decision for a stomach bypass—and his life-changing drop to 190. But fifty of those pounds gradually crept back until he finally devised a plan, stuck to it, and got his life back.

Never Going Back is Roker’s inspiring, candid, and often hilarious story of self-discovery, revealing a (now slimmer) side of his life that no one knows. With illuminating and sometimes painfully honest stories about his childhood (as the “husky” boy in class), his struggle against the odds to make something of himself, and his family life today, Roker reveals the effects that a lifelong battle with weight issues can have on a person—and how, regardless of the frustration and setbacks, you must never lose faith in yourself (just inches).

Al is telling his story to inspire others to lose the weight they’ve always wanted to lose, keep it off for good, and regain their health. He knows firsthand that it is a day-to-day process and that unrealistic diets rarely work (he has tried most of them!). And, most important, he knows that losing weight is as much—if not more—a state of mind as of body. That’s why he’s here: to recharge your willpower and see you through it like a friend—with warmth, humor, and a healthy new outlook on life.

Never Going Back is Roker’s inspiring, candid, and often hilarious story of self-discovery, revealing a (now slimmer) side of his life that no one knows. With illuminating and sometimes painfully honest stories about his childhood (as the “husky” boy in class), his struggle against the odds to make something of himself, and his family life today, Roker reveals the effects that a lifelong battle with weight issues can have on a person—and how, regardless of the frustration and setbacks, you must never lose faith in yourself (just inches).

Al is telling his story to inspire others to lose the weight they’ve always wanted to lose, keep it off for good, and regain their health. He knows firsthand that it is a day-to-day process and that unrealistic diets rarely work (he has tried most of them!). And, most important, he knows that losing weight is as much—if not more—a state of mind as of body. That’s why he’s here: to recharge your willpower and see you through it like a friend—with warmth, humor, and a healthy new outlook on life.

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

- ÉditeurThorndike Pr

- Date d'édition2013

- ISBN 10 141045469X

- ISBN 13 9781410454690

- ReliureRelié

- Nombre de pages391

- Evaluation vendeur

Acheter neuf

En savoir plus sur cette édition

EUR 60,59

Frais de port :

Gratuit

Vers Etats-Unis

Meilleurs résultats de recherche sur AbeBooks

Never Goin' Back: Winning the Weight Loss Battle for Good (Thorndike Press Large Print Nonfiction Series)

Edité par

Thorndike Press

(2013)

ISBN 10 : 141045469X

ISBN 13 : 9781410454690

Neuf

Couverture rigide

Quantité disponible : 1

Vendeur :

Evaluation vendeur

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : New. N° de réf. du vendeur Abebooks566860

Acheter neuf

EUR 60,59

Autre devise

Never Goin* Back: Winning the Weight Loss Battle for Good (Thorndike Press Large Print Nonfiction Series)

Edité par

Thorndike Press

(2013)

ISBN 10 : 141045469X

ISBN 13 : 9781410454690

Neuf

Couverture rigide

Quantité disponible : 1

Vendeur :

Evaluation vendeur

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : New. New. book. N° de réf. du vendeur D8S0-3-M-141045469X-6

Acheter neuf

EUR 93,89

Autre devise